The Alchemical Imagination - Painting as Prima Materia: The Artist as Mercurius

October 2025

This piece of writing follows an alchemical structure — beginning with theory (nigredo), the dark and fertile stage of dissolution, where ideas are broken down and reimagined; descending into personal process and dreamwork (albedo), the whitening or clarifying phase in which intuitive images begin to take form; and culminating in the glimmers of metamorphosis (rubedo), the reddening stage of illumination and synthesis, where transformation becomes embodied. The writing itself mirrors the alchemical imagination: a cyclical journey through dissolution, illumination, and renewal, where creative practice becomes both vessel and the site of potential transformation.

Nigredo – Descent into Theory

For this piece of writing, I consulted Carl J. Jung’s Mysterium Coniunctionis (1963) (Vol. 14 of the Collected Works), as this gave me scope to concentrate on one of his most important and mature explorations of alchemy. Through my engagement with this text, I hoped to engage the recurring aspects that have emerged in my process: the animus, the masculine and the feminine and the union of opposites, the heart and the feminine vessel, the artist as mediator and the nature of what alchemical transformation is at its heart. These were the themes that came most strongly to the fore for me during immersive workshops in Limerick School of Art and Design as part of the MA Art Psyche and Creative Imagination in September 2025.

In the Foreword, Jung begins by drawing on Herbert Silberer’s work (Jung, 1963, p.xiv), noting the parallels between the psychic sphere and the alchemical stages of transformation — both processes leading toward wholeness or coniunctio, the sacred union of opposites. Jung writes that “alchemy affords us a veritable treasure-house of symbols, knowledge of which is extremely helpful for an understanding of neurotic and psychotic processes. This, in turn, enables us to apply the psychology of the unconscious to those regions in the history of the human mind which are concerned with symbolism” (Jung, 1963, p.xviii).

In The Components of the Coniunctio, Jung positions that across alchemical manuscripts there runs a consistent concern with the dualism of opposites — relations of attraction and love, or of conflict and separation (Jung, 1963, p.4). The masculine–feminine dyad appears repeatedly as King and Queen, Emperor and Empress, or as servus (slave) and vir rubeus (red man) with mulier candida (white woman), or as Sol and Luna, brother and sister, “who are united by the means of the art” (Jung, 1963, p.4–5). Jung’s discussion in this section describes these elements that make up the coniunction — the coniunctio oppositorum, or union of opposites — in detail with reference to alchemical texts. Their reconciliation through transformation and integration represents a coming into wholeness for the individual.

A central figure in this union is Mercurius as the “mediator making peace between the enemies or elements, that they may love one another in a meet embrace” (Jung, 1963, p.12). He is the medium that consolidates the conjunction of the opposites, the red and the white (Jung, 1963, p.12–17). For Jung, Mercurius embodies the paradoxical essence of the alchemical process — volatile and fixed, divine and demonic, a trickster spirit of change. This sets the scene for me as an artist and my own creative engagement with material process as a field of psychic transformation, where images act as mediators between inner and outer worlds.

Albedo – The Feminine Vessel and the Practice

In Mysterium Coniunctionis, the section “The Orphan, the Widow, and the Moon” unfolds as a symbolic meditation on the feminine principle as it moves through psychic transformation (Jung, 1963, p.17-36). Jung interprets these alchemical figures as personifications of inner states within the process of individuation. The Moon (Luna) embodies the reflective, imaginal soul — changeable, receptive, and bound to cycles of illumination and darkness — representing the feminine unconscious as both vessel and mirror. The Widow signifies the soul bereft of its inner counterpart, the stage of psychic mourning and separation following the loss of union between masculine and feminine principles; she occupies the dark phase (nigredo) that precedes renewal. Out of this desolation emerges the Orphan, the vulnerable child of transformation, symbol of psychic rebirth and the earliest form of the Self newly born from the dissolution of opposites. Together, these figures trace a feminine alchemical sequence of separation, mourning, and regeneration, revealing that loss itself becomes the ground of renewal, and that the lunar, fluid, and relational aspects of the psyche hold within them the capacity for rebirth and wholeness.

Jung writes of the prima materia in its feminine aspect:

“It is the moon, the mother of all things, the vessel; it consists of opposites, has a thousand names, is an old woman and a whore, as Mater Alchimia. It is wisdom and teaches wisdom, it contains the elixir of life in potential and is the mother of the Saviours and of the Filius Macrocosmi. It is the earth and the serpent hidden in the earth, the blackness and the dew and the miraculous water which brings together all that is divided. The water is therefore called ‘other,’ ‘my mother who is my enemy,’ but who also ‘gathers together all my divided and scattered limbs’” (Jung, 1963, para 15, p.21).

This passage captures the full ambivalence and depth of the feminine in alchemy: she is both container and content, mother and enemy, decay and renewal. The materia is the living psychic ground of transformation — fluid, paradoxical, and creative. To hold this within oneself is to become the vas hermeticum, the vessel in which the opposites are dissolved and reborn. The feminine thus represents not a passive receptacle but the terrain of psychic integration: the capacity to hold tension and fragmentation until they coalesce into new symbolic life.

Jung later writes,

“By heart is signified love, which is said to be in the heart, and the container is put in the place of the contained; and this metaphor is taken from the lover who loves his beloved exceedingly much, so that his heart is wounded with love” (Jung, 1963, para 25, p.32).

Here the vessel becomes the heart itself — the place where love, pain, and psychic transformation coexist. The container put in the place of the contained describes the feminine paradox precisely: she is both the holding and the held, the wound and the healing. As an alchemical image of the feminine, the heart signifies an emotional vessel that gathers and reconciles what has been divided, just as the prima materia gathers the fragments of the psyche. The feminine, in this sense, is the ground of love as the transformative medium that unites all opposites within the human soul.

Albedo to Rubedo – Practice as Transformation

In a workshops with Lyn Mathers (26/09/2025) somethings were particularly resonant and present.

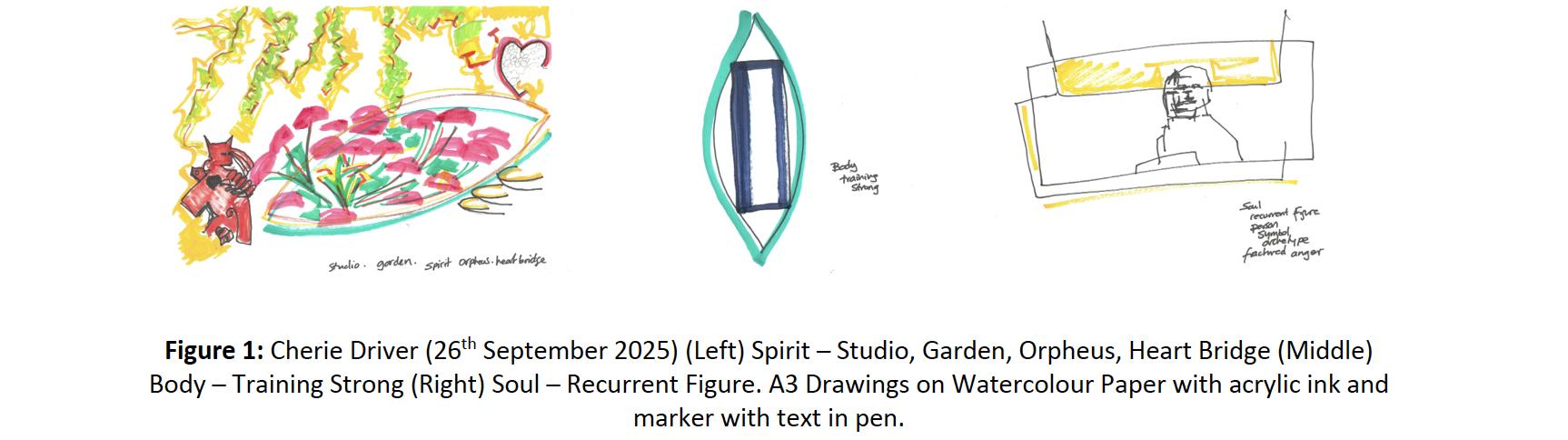

My Spirit drawing (Figure 1 – left) brings together the studio and the garden — the two spaces where I feel most alive, rooted, and connected to something larger than myself. Both are living spaces of making and tending: one material, one psychic.

The reds and pinks are flowering energy, invoking the garden itself, while the golden vines (seen through the window of my studio) dancing through threads of light hold everything in relation (photo 1). The small red figure with his black heart is an animus figure, a drawing of a stone statue carving that I have at my front door (photo 2). The red heart on the right, is a drawing of a stone carving of a heart bridge now place at my studio wall (photo 3). Orpheus refers to text on the bricks that lie close to both locations (photo 4). Orpheus had been the name of the old art college building in Belfast where I trained as a student. When the building was demolished, students sold these bricks inscribed Orpheus as emblems of something significant and lost but not forgotten. Orpheus represents the artist who moves between worlds, holding love as a guide through darkness. When I made this drawing (figure 1 – left), I felt that the heart was the bridge — the crossing between inner and outer, art and spirit, grief and beauty. The spirit here is not lofty or abstract; it is embodied in colour, gesture, and the daily tending of creative life.

The Body drawing (Figure 1 – middle) emerged from how physically grounded I have felt lately — through strength training, through movement, through recognising the body as an instrument of will and containment. The almond or vessel shape came intuitively: a protective form, but also one that pulses with energy. The dark centre holds power, discipline, and stability; it is where effort transforms into confidence. I see this as an image of the vas hermeticum — the alchemical vessel, but also the body itself, holding psychic and physical tension until it becomes strength. The making this drawing came from a place of physical strength. The body here becomes the site of transformation, a reminder that the work of individuation is not just inner psyche, soul and spirit but muscular, cellular, lived.

The Soul drawing (Figure 1 – right) came from a dream that has stayed with me vividly. I saw a man behind a kind of screen — it could have been glass or a car windscreen — his face fractured with light and anger. The image shifted suddenly from dream into movement, as if it had become animated, and I woke with a jolt. It felt alien, electric, unsettling, as though something from the unconscious had crossed over and revealed itself too sharply. When I drew him, I wanted to hold that strangeness — the sense of containment and the trembling edge of rupture. The yellow band of light feels both like illumination and division. This figure is not simply a person; he feels symbolic, an archetypal animus energy returning in a fragmented, volatile form. I sense he represents the part of the psyche that seeks recognition, that carries anger and unmet force. The drawing tries to meet him, to frame what resists framing. He remains both distant and near, a figure of soul encounter.

Together, these three works trace a movement through spirit, body, and soul — from the heart’s field of creation, to the strength of embodiment, to the psychic confrontation with what lies beyond conscious control. Each drawing is a vessel: a place where I meet the energies that move through me — nurturing, strengthening, disturbing — and give them form. This was a very powerful and insightful workshop that in many ways framed the work that followed and gave me some clarity on things I needed to give further attention to.

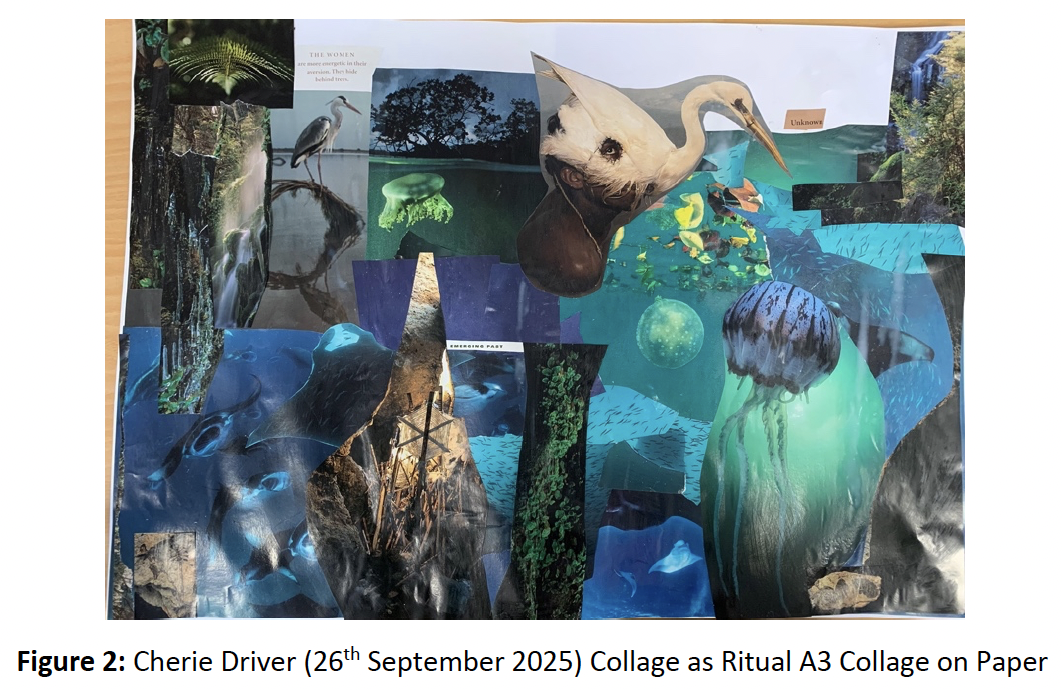

This collage (Figure 2) emerged in a workshop as an act of ritual — a descent and a surfacing. I approached it as I approach sea swimming: by surrendering to immersion and what came to me as I gathered images that spoke to me during the process. The deep blues, greens, and luminous aquatic forms drew me back to Brompton Bay, where I swim through all seasons. Making it, I felt the same quiet joy and alertness I experience in water, especially during the summer when I swam among jellyfish — creatures both fragile and fierce, transparent yet pulsing with life.

An inner cave opens in the lower part of the collage — a darkened threshold where memory, depth, and transformation converge. It feels like a psychic chamber, a place of gestation, perhaps even the vas hermeticum of the feminine unconscious that my research continually circles. Around and within it, there are traces of landscape and organic growth: roots, corals, vines, and phosphorescent plants that suggest both decay and renewal. The natural world seeps into the dream world here, merging the outer environment of swimming with an inner terrain of feeling and being.

At the centre, the hybrid male figure with the bird mask watches over this submerged world as the Herron also does. I recognise him as an animus figure — ambiguous, part guardian, part intruder — a presence that provokes curiosity and reflection. He belongs to the realm of the Unknown, mediating between instinct and imagination, matter and spirit. Through layering and cutting, I found myself constructing a visual vessel — an alchemical vas, a psychic sea-cave — where fragments of nature, body, and image are held in relation. The collage became a ritual of return to the element that sustains me: water as psyche, movement as renewal, art as breathing underwater.

Rubedo – Transformation and Metamorphosis

Between days, I had a vivid dream of a male archetype — an image that seemed to shudder between containment and eruption. He felt both deeply familiar and alien, a figure of the animus transformed. This dream remained with me the following morning, linking to earlier archetypal male presences that had appeared in dreams and drawings from the past. In my account of the dream to the group, I know on a deep level I had invoked an old line of grief of not having a counterpart, an echo of an earlier dark phase (nigredo) that precedes this current phase which is of renewal. During the alchemical activity day, and in response to this, I felt compelled to cross into the park and gather materials that spoke to me — holly, red berries, seeds, mushrooms, cones, wood, conkers, and red leaves. These became a living constellation of the prima materia: matter in its raw, transitional form.

When I returned to the gallery and art room, I arranged the materials intuitively, almost ceremonially (Figure 3). The act of making a small alchemical solution — olive oil, berries, crushed hazelnut, salt — felt like participating in the ancient logic of coniunctio: the bringing together of opposites, the marriage of earth and spirit. I prepared the glass vessel carefully, cleansing it and removing the residue of an old label, as if stripping away psychic residue. The vessel stood open in the afternoon, to the air, a living vas hermeticum — a site of slow transformation and atmospheric exchange.

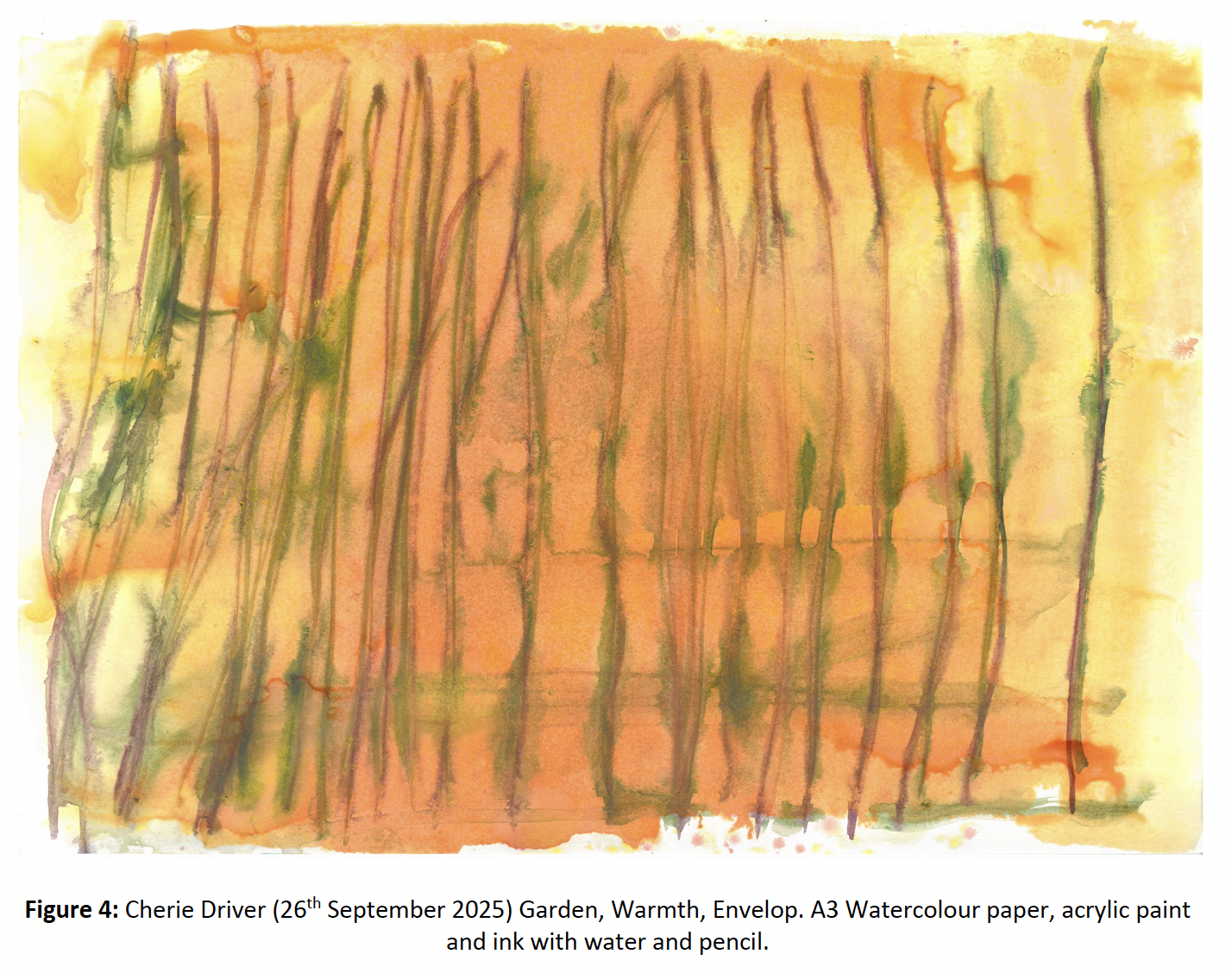

In this moment, art-making became indistinguishable from ritual. The process echoed the red stage of the rubedo, the phase of illumination where the opposites begin to unify and the work glows with inner fire. As in the alchemical texts, the vessel becomes not only the container of change but the soul’s own body. The materials, like pigments on paper, are transformed through contact, attention, and time. This resonated through the Garden, Warmth, Envelop work that I made that day on paper (Figure 4).

James Elkins articulates this mystery process with precision:

“Painting is metamorphosis. When people say art is alchemy, they usually mean it involves metamorphoses that can only be partly understood […] Alchemy is the generic name for those unaccountable changes: it is whatever happens in the foggy place where science weakens and gives way to ineffable changes” (Elkins, 2000, p.116).

This describes exactly the terrain of my current practice (Figure 5) after my return to the studio following my trip to Limerick — that foggy place between the visible and the ineffable. Each drawing and collage unfolds as a metamorphic act, a living process of coniunctio between matter and psyche. The pigments, water, and paper become the prima materia — unpredictable, fluid, alive — while I am both the observer and the one inside the vessel. The work of art becomes the vas, holding tensions until they resolve into new symbolic form.

Painting and drawing are not illustrations of transformation; they are the transformation — the lived alchemy of becoming. What takes place within the studio mirrors the psychic opus: dissolution, encounter, and reconstitution. The artist, like Mercurius, moves between worlds — mediator, witness, and participant in the mystery of change. As Elkins observes, “it is not always certain whether the adept is in the laboratory, watching the vessel, or inside the vessel, looking out […] Artists know the feeling that others can only weakly imagine, of being so close to their work that they cannot distinguish themselves from it” (Elkins, 2000, p.162). In this sense, the artist becomes both the alchemist and the matter undergoing transformation — the container and the contained. The studio itself becomes a vas hermeticum, where the prima materia of experience, emotion, and imagination are continually dissolved and reformed through the practice of making.

Art, like alchemy, is never static; it is a living process of renewal. The work glows with the residue of its own psychic fire, carrying traces of the invisible exchanges between matter and spirit. Jeffrey Kiehl articulated this so well in his lecture Jungian Alchemy and Transformation within the Masters in Art Pscyhe and the Creative Imagination (8th of October 2025) and particularly in response to some questions I asked him at the end. One was; how might the material process of making art be understood as an alchemical act of transformation? His response was; “you are working with matter, so that is alchemy, you are transmuting that […] imagination […] you are getting in a relation with psyche, so you can get yourself out of the way […] the dissolution, calcination, the freeing up of that which is in you and wants to come out, materialise itself, so you are in relationship with it […] the work of art” (Kielh, 2025, Online Zoom Recording 08/10/25).

Therefore, and in final reflection, each mark and gesture becomes evidence of the psyche’s dialogue with the world — a visible echo of the inner coniunctio, the sacred union of opposites that unites matter and spirit within the soul. In this way, creative practice becomes not merely a reflection of the alchemical imagination but its enactment: the rubedo of consciousness, where the heart, like gold, is tempered and transfigured through the act of creation.

This closing movement circles back to Jung’s description of the prima materia in its feminine aspect and to the heart as vessel — the place where love, pain, and transformation coexist. Within the vas hermeticum of artmaking, all that has been divided or wounded is gathered and renewed. Here, the artist takes on the role of Mercurius — the mercurial mediator and trickster spirit of change — moving between opposites, translating matter into spirit and spirit into form. The studio becomes a living container of the coniunctio oppositorum. Through this work, the sacred marriage of inner and outer, masculine and feminine, conscious and unconscious is continually re-enacted — a living alchemy in which I, the artist, like Mercurius, becomes both messenger and medium of transformation and the heart becomes the vessel through which the opposites unite in love and renewal.

References

Elkins, J. (2000) What Painting Is: How to Think About Oil Painting, Using the Language of Alchemy. New York: Routledge.

Jung, C.G. (1963) Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy. The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol. 14. Translated by R.F.C. Hull. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Kiehl, J. (2025) Jungian Alchemy and Transformation. [Online lecture] Delivered 8 October 2025, MA Art, Psyche and the Creative Imagination, Limerick School of Art and Design.