A Revolution Starts as a Whisper: The Ecological / Eco-psychological Self (November 2025)

A revolution rarely begins with thunder. More often, it begins with a whisper — subtle, intimate, almost imperceptible. A whisper that passes between self and other, psyche and world, consciousness and the more-than-human. This quieter register of communication is where the ecological self first stirs. It is the mode through which we begin to listen differently, to sense differently, to perceive the world not as object but as interlocutor. This whispering, relational quality is embedded throughout Arne Næss’s notion of the ecological self and resonates deeply with Jungian depth psychology, ecopsychotherapy, and with my own creative practice.

Næss proposes that the human self is radically more expansive than Western psychological and philosophical traditions have allowed. Rather than a bounded ego, he describes an identity rooted in the living world, emerging through processes of identification, relationship, and interdependence. In this broader conception, “We may be said to be in, of and for Nature from our very beginning” (Næss 2005a, p. 35). The ecological self is therefore not something added onto the ego but something uncovered — recognised — through what Næss calls “allsided maturing” (p.35). This maturing is not a singular movement but a rhythmic back-and-forth; one could say it emerges as a whisper between the human and the more-than-human, the quiet reciprocity that grows as we learn to listen.

Næss argues that joy and meaning increase through self-realisation — the unfolding of each being’s potential (2005a, p. 35). This unfolding is sustained by identification: the capacity to recognise our continuity with others, human and nonhuman. Drawing on Erich Fromm, he emphasises that genuine love is indivisible. The love we cultivate for ourselves is inseparable from the love we extend to others and to the world, for “genuine love… implies care, respect, responsibility and knowledge” (Fromm as cited in Næss 2005a, p. 36). In this sense, the ecological self is not an abstract metaphysical proposition but a lived ethical stance — one that grows through deep relational listening. A revolution begins here: quiet, relational, and interior.

Jungian depth psychology offers a parallel understanding of the self as something vastly larger than the ego. For Jung, individuation is the process by which the ego comes into relationship with the Self — the archetype of wholeness that includes both consciousness and the unconscious (Jung 1951). This dialogue between ego and Self, conscious and unconscious, is often subtle, indirect, symbolic. It moves like a whisper through dreams, images, intuitions, bodily sensations. Here too, the psyche calls us into deeper relation — not through command but through invitation.

Mary-Jayne Rust extends this conversation through her concept of the ecopsychological self and the ecological unconscious. She argues that the psyche cannot be understood without its embeddedness in the Earth and that psychotherapy must respond to this relational reality. Rust describes the larger field in which we live as “an energetic system, both matter and spirit at once, which has its own intelligence” (Rust 2004, n.p.). This intelligence communicates not primarily through linear reasoning but through atmospheres, images, sensations — through whispers. Rust suggests that “the ecological self and ecological unconscious are developing a language to describe their relationship to other parts of the self” (Rust 2020, p. 112). The emergent nature of this language mirrors the gentle act of listening required to hear it.

In my own research at the intersection of depth psychology, myth, and contemporary art, these ideas resonate profoundly. My practice has long been attuned to the feminine symbolic — that dimension of psyche associated with receptivity, intuition, cyclicality, and interconnectedness. The whisper is a distinctly feminine mode of communication: less declarative, more invitational; less about mastery than attunement. It aligns with how I work in the studio, where painting becomes a site of dialogue rather than assertion.

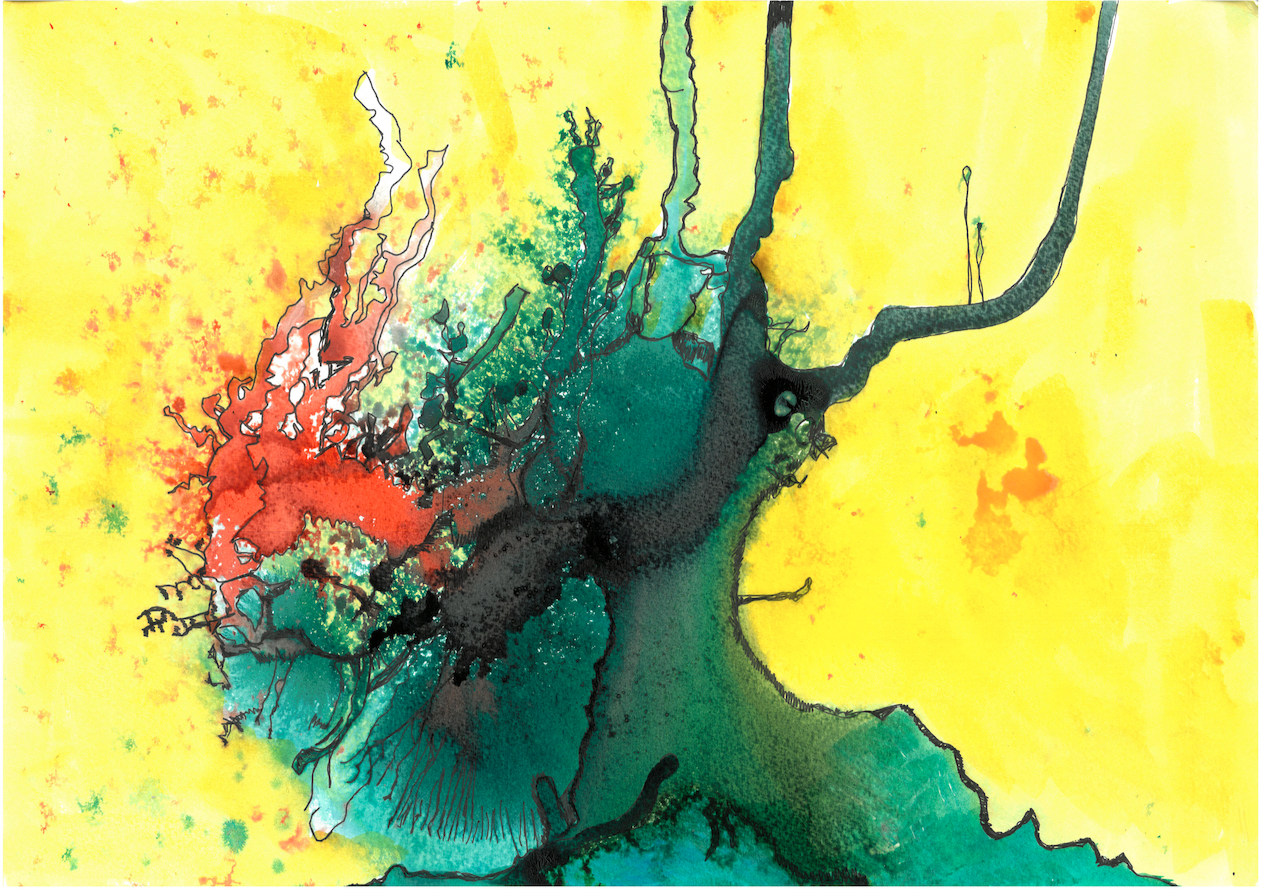

Figure 1 Cherie Driver 8/58 Dialogue Works, Ink, acrylic, pen and pencil on A3 watercolour paper, 2025

Figure 1, 8/58 Dialogue Works (Ink, acrylic, pen and pencil on A3 watercolour paper, 2025), exemplifies this process. The image emerges not from a predetermined plan but from a listening stance — a quiet waiting for the line or wash to reveal itself. This daily dialogue with material, gesture, and feeling is itself an ecological practice. The painting becomes a threshold space where internal and external worlds meet, where the psyche whispers itself into form in conversation with the grain of the paper, the movement of the hand, the atmosphere of the room.

Figure 2, Studio. Photograph by Cherie Driver 13 November 2025

This whispering relation is also evident in the studio environment. Figure 2 shows fourteen of my daily dialogue paintings pinned to the studio wall, while light from the garden projects faint images of foliage onto the surface. These shadows become a second layer of whisper — the garden speaking into the studio, the outside world entering the interior workspace as a quiet presence. The garden deepens the relational field and it grounds the studio in materiality. The studio, the light, the foliage, the paintings — all participate in a quiet conversation that shapes my sense of self. This is the ecological self not as theory but as lived, embodied process.

The repression of this relational, whispering dimension parallels the ecological crisis itself. Modernity’s dissociation from nature mirrors the ego’s inflation and its repression of the unconscious. As the human asserts mastery, the whisper becomes harder to hear. The shadow grows louder in ecological collapse, psychic fragmentation, and cultural alienation. The ecological shadow, in this sense, is the unacknowledged truth that we are not separate — the denied awareness that our wellbeing is bound to the more-than-human world.

Rust’s ecopsychotherapy responds to this by restoring the conversation. She situates therapeutic work within a field where inner and outer realities mirror one another (Rust 2004). The ecological self, like Jung’s Self, is not fixed but emergent — an unfolding process of dialogue. This dialogical movement resonates strongly with my art practice, where making becomes a form of imaginal listening. As Hillman (1995) suggests, aesthetic contemplation is a way of restoring soul to the world. In the studio, this takes the form of attending to what wants to appear — a brushstroke, a colour, a shadow. Each is a whisper from the ecological unconscious.

Through this lens, the ecopsychological self can be understood as an ecological individuation: the integration not only of psychic opposites but of the split between human and nature, matter and spirit, inner and outer. It invites us to inhabit a more porous, participatory mode of being. Art becomes a site for this transformation — not as a personal act of expression but as an ecological event where multiple agencies meet.

To live from the ecological self is to cultivate the capacity to hear the world whisper again — to recognise the intelligence of stone, water, light, and shadow. It is to participate in a psychology with soul, as Hillman (1995) describes, where the world itself is alive and speaking. And if a revolution is to come — a revolution of consciousness, of relationship, of ecological healing — it may begin not with grand declarations but with this: a whisper between self and world, human and more-than-human, ego and Self. A whisper that calls us back into relationship, into intimacy, into responsibility. A revolution that starts, as most true revolutions do, quietly.

References

Fromm, E. (1956) The Art of Loving. New York: Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1995) A Blue Fire. New York: Harper Perennial.

Jung, C.G. (1951) Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Næss, A. (2005a) ‘Self-realization: An Ecological Approach to Being in the World’, in Glasser, H. and Drengson, A. (eds.) The Selected Works of Arne Næss: Volume X. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 515–530.

Roszak, T. (1992) The Voice of the Earth. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rust, M.-J. (2004) ‘Creating Psychotherapy for a Sustainable Future’, Psychotherapy and Politics International, 2(1). Available at:http://www.rainforestinfo.org.au/deep-eco/mj2.htm (Accessed: 10 November 2025)

Rust, M.-J. (2020) Towards an Ecopsychotherapy. London: Confer Books.